How we created an interface for broadcasting helisport competitions

Helisport Federation requested our assistance in creating a system of electronic judging.

Helisport competitions involve execution of several events. One of the most complicated is the Precision Flight. The task is to fly a certain stretch (corridor) within a set time, carrying an attached load (a beacon) so that the beacon doesn’t cross the corridor’s vertical and horizontal boundaries. In addition to this, the competing team has to perform a number of other elements such as turns, 360º turnaround, sideways and backwards flight, etc.

Prior to the start, each team has 300 points. This is the maximum result that the team may get if it avoids all the fines. The event’s result is calculated by subtracting the sum of fines from 300 points.

The two main reasons for creation of the electronic judgement system were as follows:

- To minimize the human error factor, because at that moment the judges had to eyeball whether the helicopter’s beacon crossed the corridor’s boundaries. This obviously created many mistakes, inaccuracies, and disputes.

- The audience was bored because at a distance of 300 m from the competition area they couldn’t see and understand how well the team was executing the event.

Plus, we were tasked with solving two other problems:

The lack of real data – when we started developing interface, the tracking system wasn’t yet operational, and we couldn’t receive the beacon’s coordinates in three-dimensional space.

The absence of starting point and complete uncertainty – we were solving a unique problem, and we have yet to find any precedents or alternatives.

Collecting information

On a sunny day in May, we flew to the Konakovo aerodrome and spent a whole day there, watching the competitions together with the audience. It was important to understand what the audiences see during the events, and what happens at the briefings’ hall and beyond.

We went through dozens of different broadcasting interfaces – from aeromodelling to yachting – studying the principles of displaying various data points.

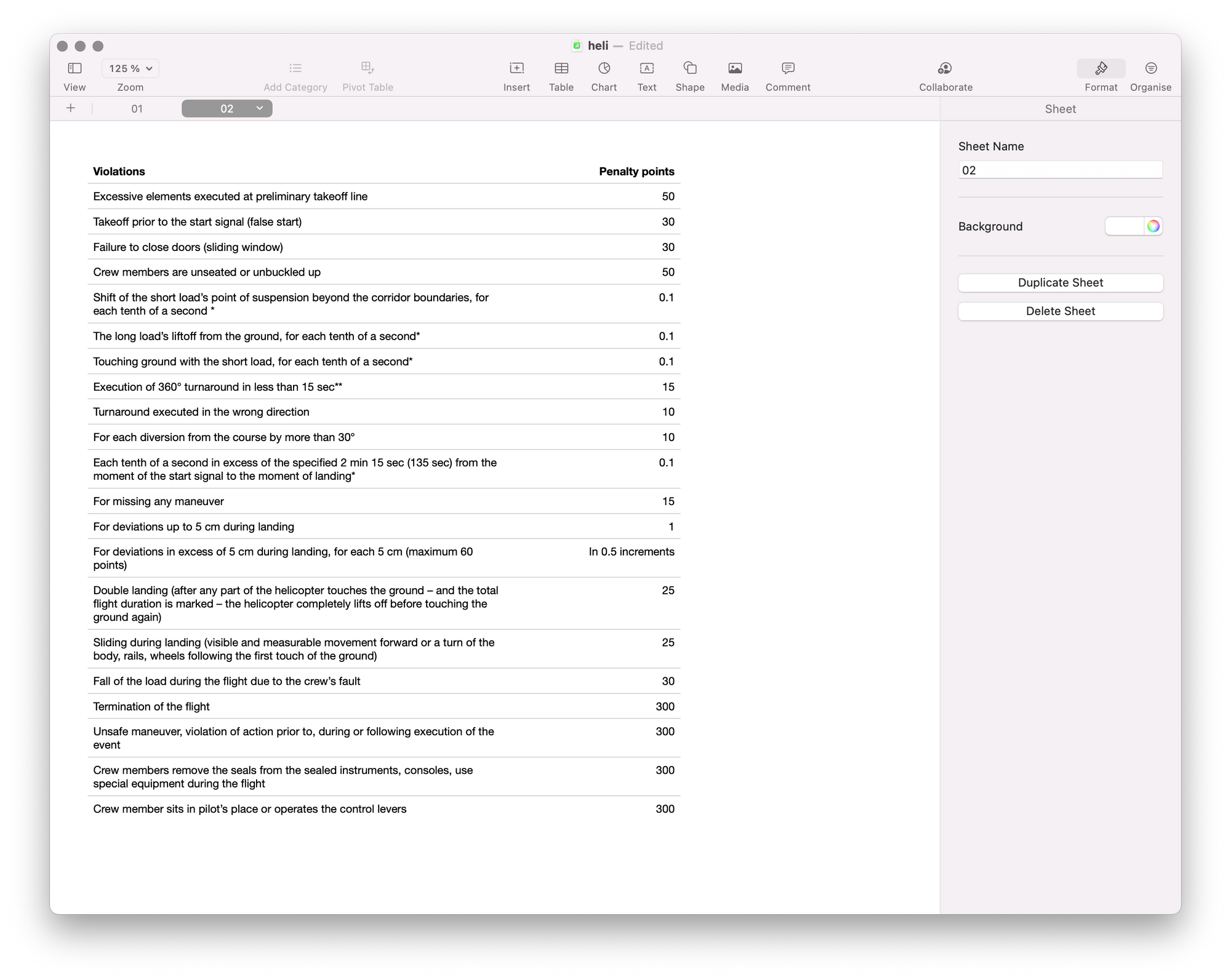

We learned by heart the massive volume with competition regulations detailing the rules of event performance. The Precision Flight event has several dozens of penalties, and we had to make sure that the interface took all of them into account – even something as small as the helicopter’s open sliding window:

Happily, we were provided with a mentor on all the issues of event execution – Andrew, master of helisport – whose mastery of this event is truly uncanny. Thanks to Andrew, we learned all the subtleties that you won’t find in the books.

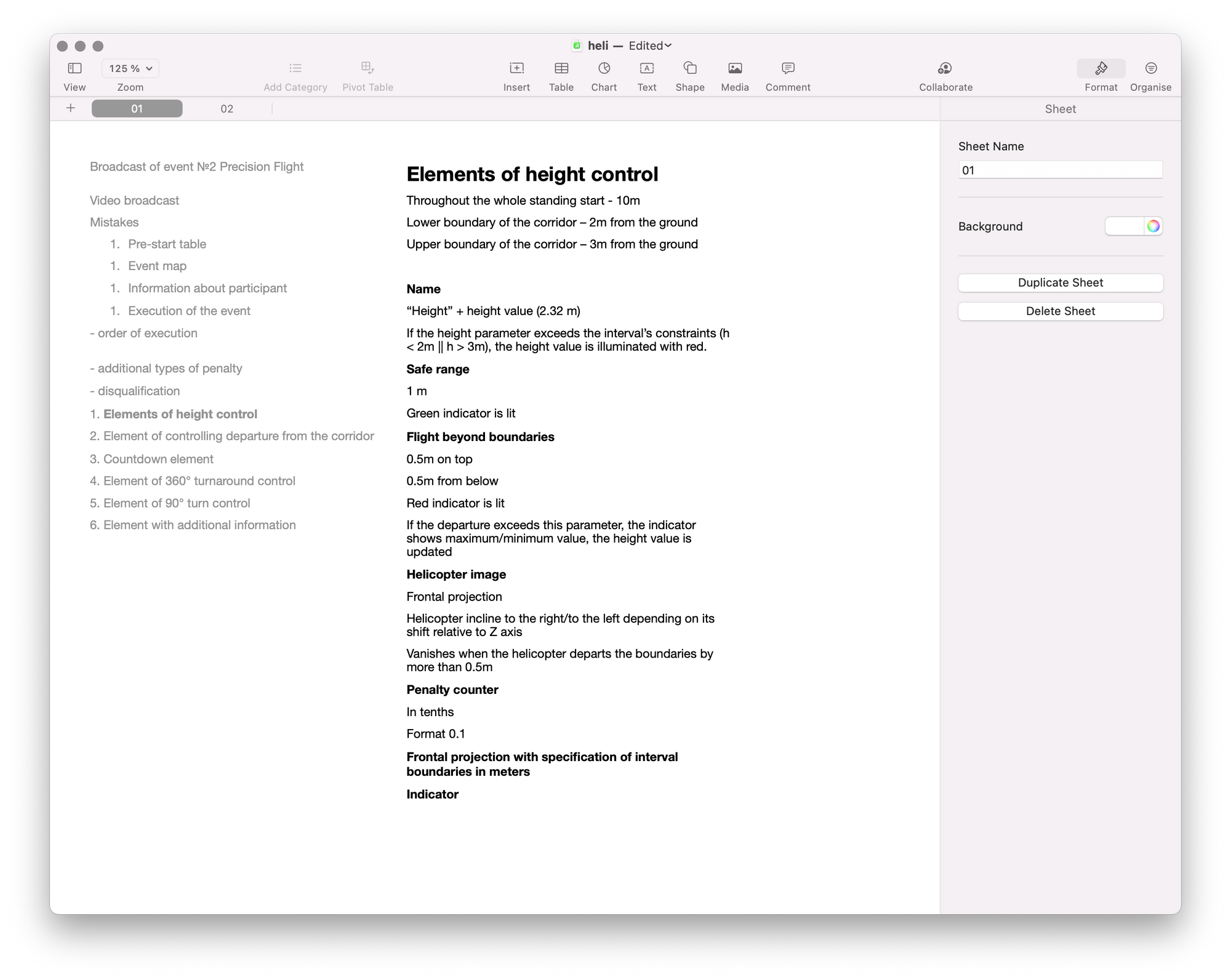

In order to collect all the requirements and to document them, we divided the event’s broadcast into components and described each of them:

First iteration

We decided that the video broadcast is the principal task here, while the graphics are secondary. On the other hand, the graphics had to be an independent component that reflected the essence of the event.

Our graphics’ principal components would be the visual elements that reflected the beacon’s position relative to the corridor.

The first element is responsible for the corridor’s height, and the second – for its width. Each element has its own counter of penalties that switches on if the beacon ends up outside of the set corridor.

Each tenth of a second that the beacon is flying outside of the corridor means one tenth of a point taken off as a penalty.

In the first approximation it looked like this:

It was difficult to judge the interface’s behavior using static pictures, and so we decided to develop an interactive prototype. We wanted to make sure that events on the screen could be comprehended even by those who were watching the broadcast for the first time in their lives, unfamiliar with the event’s rules.

Prototype

Since the beacon tracking system was still under development, we had no real data to use in creating the prototype.

In order to imitate helicopter’s flight in three-dimensional space, we used the Leap Motion controller. It’s a small device that reads the palm’s movement in space and conveys its coordinates. Fortunately, Leap Motion SDK contains a JavaScript library that we connected to the Framer.

The integration went well, and we were able to control the height for the first element and width for the second:

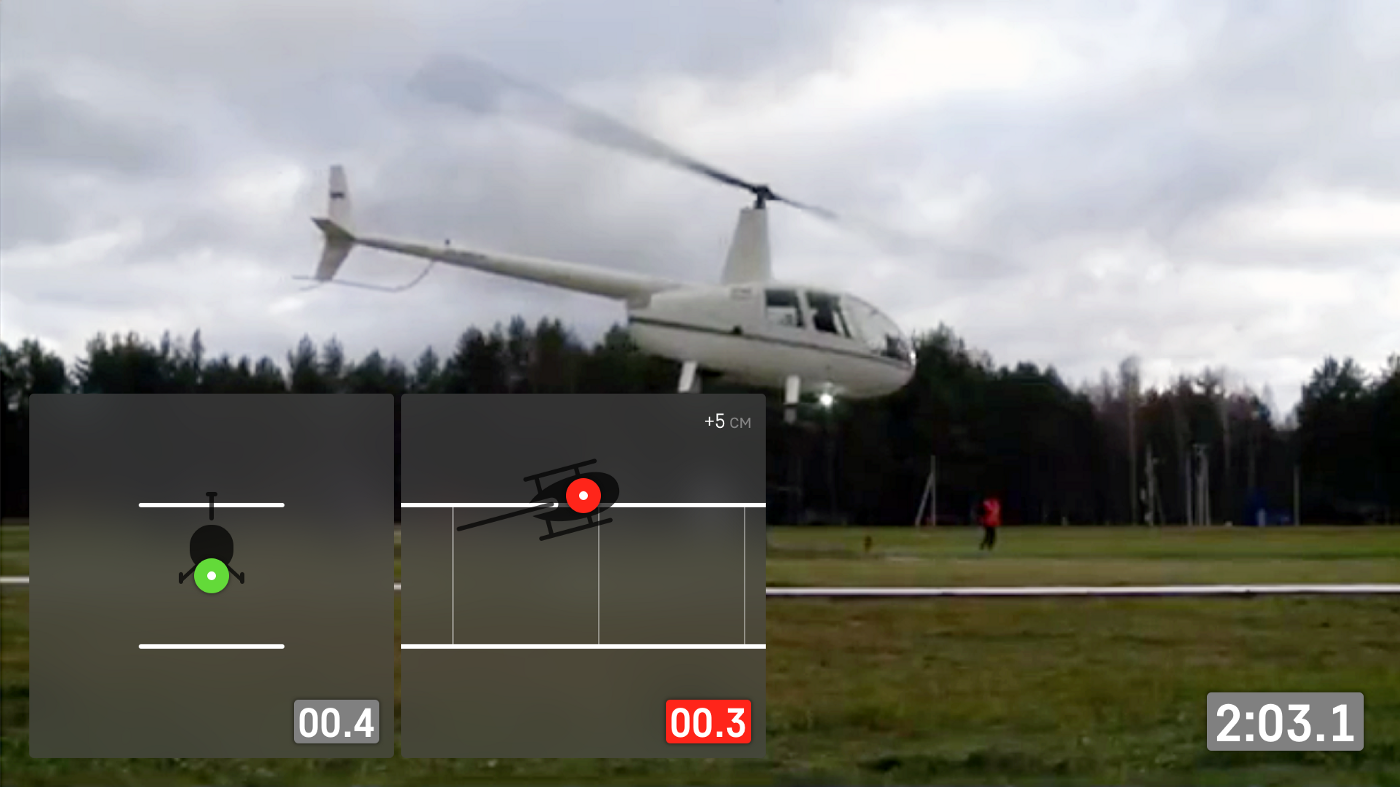

We took a pre-recorded training video and superimposed our interface on top of it. This is how the first approximation looked in real time:

We showed the clients our first attempts: the principal idea with two visual elements seemed promising, and we decided to stay with it, working in more detail on different states and making the graphics more legible from a greater distance.

Next steps

We added the general counter of points, made the visual elements round so that they would visually resemble the helicopter’s panel of instruments. Then we decreased the size of the elements because it turned out that the previous size hid the image of the helicopter itself.

At this point, we received a very important comment from Andrei who told us that the helicopter couldn’t depart from the corridor for more than 0.5 m. This helped us to calculate the optimal size of the elements and the helicopter in a way that allowed to accommodate 99.9% of all cases.

In the previous iterations, we placed the helicopter inside the element, leaving the corridor fixed. Now, the helicopter was fixed, while the corridor moved along. This greatly increased “readability” of the elements and of interface as a whole.

And the most important innovation: when a mistake was made, we replaced the red beacon with highlighting the side of the corridor where the mistake was made. That made it even more intuitive and visible even to those looking at the screen sideways.

We added the counter of penalties for each side. The element that controlled the corridor width ended up having four of them, because this element was responsible both for the corridor width and for the helicopter’s turnaround above a square with a size of 1x1 m, where the machine could end up out of bounds on 4 sides of the square.

We elaborated on the rare instances when the helicopter may depart from the corridor boundaries by more than 0.5 m. Following some cosmetic changes, the elements now looked like this:

That wasn’t all

In addition to the graphics that would reflect the flight through the corridor, we needed to come up with graphics conveying the execution of turns. The 360º turnaround in a set direction has to be executed within the boundaries of a landing with an area of 1x1 m, while the duration of the turnaround should not be less than 15 seconds. At the start of the turnaround, the interface launches a timer (full circle is 15 seconds) that reflects the required direction of the turn. If the crew executes turnaround too fast, it’s reflected on the screen immediately:

Homestretch

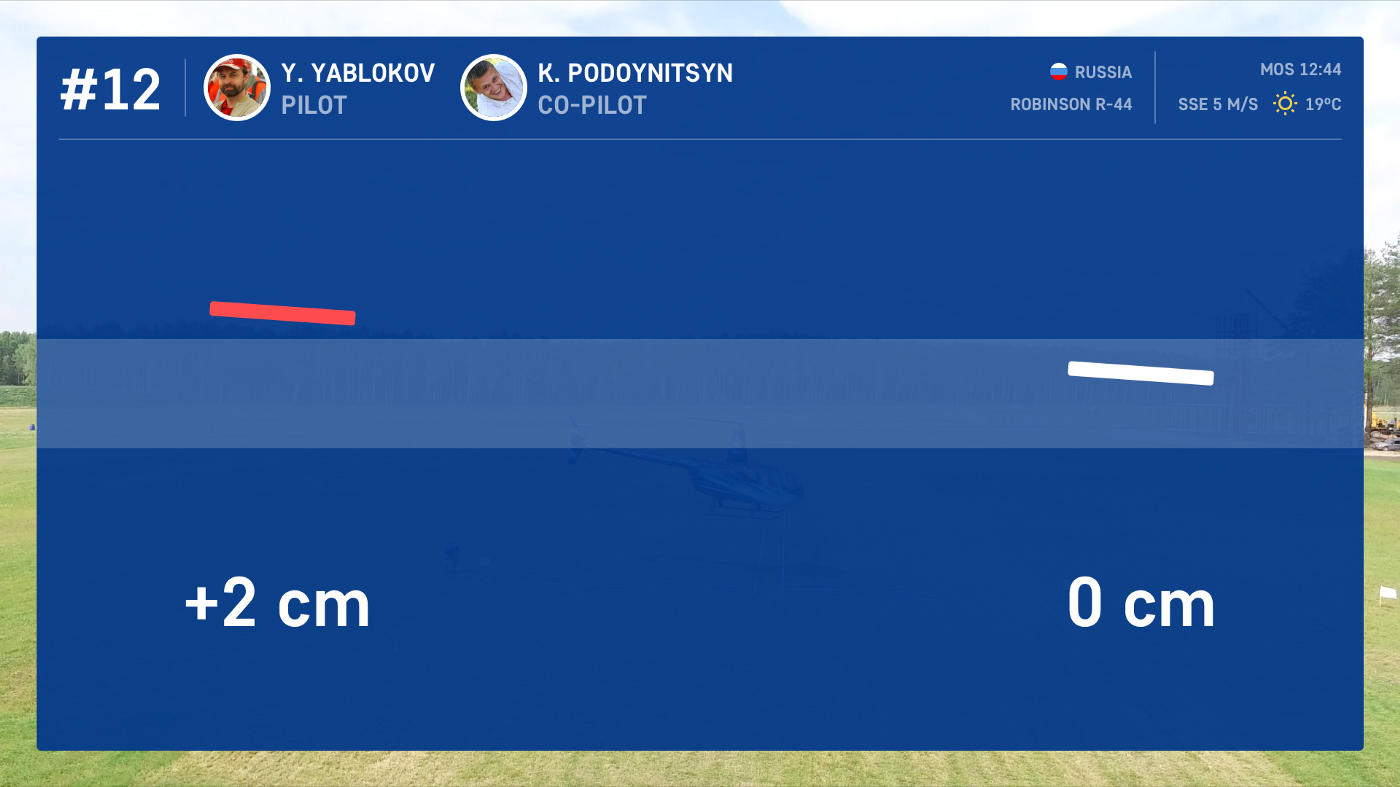

A separate stage of the event is the landing. A line with a width of 5 cm is marked on the landing pad, and the helicopter has to land on that line with special marks on its landing gear (the width of the mark is 1 cm).

The judges determine the marks’ position relative to the line with the help of a ruler, so this process takes some time before the results appear on screen.

To keep the audience entertained during the measuring process, we added the animated video tracking event’s execution and highlighting all the mistakes that were made.

Following the measurements, we show the results on-screen:

Following that, we show the team’s current position:

And give the summary table:

The result

It took us exactly 5 weeks to develop and document the first version of the interface. Each week, we demonstrated our progress and explained which decisions were made and why.

In a short period of time we were able to create the MVP that satisfied all the original requirements. Moreover, the broadcast interface now performs two important functions:

Provides tutoring for the viewers unfamiliar or poorly familiar with the event’s rules.

With the help of the interface, the teams can track their mistakes and draw the relevant conclusions for the future.

We decided that we’ll work on the interface’s final style after we develop the graphics for the competition’s other five events. There’s still plenty of work ahead :)

Final video: